Knowing me well, as she does, my darling mother bought me a voucher for a tea-tasting experience for my birthday last year. Knowing my powers of organisation as she does, she was not remotely surprised when it took me over seven months to cash it in. But good things come to those who wait, and in due course, I strolled eagerly up to the Langham Hotel on Regent Street to spend the afternoon with Blends For Friends’ expert tea taster and master blender, Alex Probyn.

In recent decades tea’s supremacy in England came into question, seeing it frequently dismissed as sophisticated coffee’s country cousin. But with the rising ‘vintage’ trend, the humble cuppa is once again becoming ‘cool’ – evidence of this even as I made my way up Regent Street was the new T2 flagship store, all achingly hip neon and black signage and artfully displayed crockery. Tea shops, tea rooms and tea parties are popular with the young as well as the old.

Now, me and tea: it’s a lifelong love thing, not to say an obsession. In this I am classically British. In these isles, laying on a round of the cup that cheers but not inebriates is the most surefire method of gathering a family together, bonding with your colleagues, or demonstrating the sort of workaday, wordless devotion that underlies the most authentic love matches. Say “Cup of tea?” in almost any scenario, and the response will always be “ooooh, lovely!” It’s very typical of our buttoned-up, ‘careful now’ country that our greatest shared national indulgence should be such a modest one. As Bill Bryson, my favourite anglophile American, noted bemusedly, “I remain impressed by the ability of Britons of all ages and social backgrounds to get genuinely excited by the prospect of a hot beverage.”

My memories of tea go back to my childhood, when my grandmother would make pots of the stuff on a more or less continuous basis all day every day, winter or summer, and saw no reason why she shouldn’t introduce her little granddaughters to the wonders of caffeine nice and early. Whenever someone makes me an extra-milky cup, or accidentally gives me sugar, I have Proustian memories of the mug with yellow flowers which was ‘mine’, and how she would call the bubbles on the surface made by the flow of tea from the pot (always from a pot) ‘kisses’. Nowadays, I like my tea strong enough to climb out of the pot by itself, and scoff at the idea of sugar. I might even entertain a green tea or a (whisper it) herbal infusion. But while my palate may have matured and diversified, my love for the brown stuff remains childlike if only in its insatiable greed. So I knew that I was in for a treat.

Having navigated the Langham’s intimidatingly luxe reception, I found myself seated at a table with a handful of strangers, waiting for the show to begin. Probyn was already presiding over a table laden with gleaming pots and sample shots of tea. This wasn’t like other ‘gift activities’ I’ve attended in the past, where the emphasis was on having fun. Quite apart from the intimidating levels of glamour at the Langham, the atmosphere was unapologetically aimed at aficionados – Probyn’s apparent idea of an icebreaker to put people at their ease was to ask the room if anyone had a favourite tea plantation (and alarmingly, one of our number did). I pulled out a notepad and tried to look serious, all the while wondering when we would be getting a cup of tea.

Alex began with a potted (hah) history of his life in tea. Ironically, he didn’t even drink tea before being employed by Tetley as a graduate trainee tea-taster 17 years ago (and by the way, who even knew there was such a job? And why didn’t you tell me???)

Having applied as a joke and getting the job almost on the strength of his inexperience, he fell in love with the tea industry, eventually shifting from tasting to sales and marketing with a view to gaining the skills and experience he would need to set up his own business, Blends For Friends – a bespoke tea-blending service creating individual blends from over 750 ingredients. This was the end-game of today’s tea-tasting experience – we would try a wide range of teas, learn about how different ingredients worked together, and then finally design our own blends of tea which Alex would then go back to the lab and create for us.

He then moved on to the history of tea, taking us on a guided tour of 5000 years of camellia sinensis, from its mythical origins in China, when a leaf dropped by chance into the Emperor’s cup of hot water. The ancient Chinese tea trees were much taller than the bushes on plantations today, having not been cultivated, and initially monkeys were trained to pick the delicate ‘tips’ (as in PG, simply the top two leaves and the bud of the tea plant) from the tops of the trees – you can still buy ‘monkey-picked’ tea to this day, for grotesque amounts of cash. He described the expansion of the tea tradition into Japan and the Far East, and its slow, circuitous route to Europe, finally reaching its spiritual home in London in the 1660s via the Dutch East India company – as in so many things, including gin, the Dutch were way ahead of us, and had been guzzling tea since the sixteenth century.

As a foreign imported product, tea was heavily taxed, but as its popularity grew, this became unsustainable – tea smuggling was rife, and the smugglers would often adulterate the blend with whatever came more easily to hand, principally sheeps’ droppings. Pitt the Younger conceded defeat and lowered the tea tax in 1785. In later years, the British Empire sought a more economical source for its citizens’ immoderate lust for the brown stuff by furtively exporting grafts of tea plants from China with a view to transplanting them to its colonies in India; only to find the Indian farmers much amused at being solemnly charged with cultivating a plant that had been growing ignored all over the subcontinent for as long as anybody could remember. Imperialism fail.

Since then, tea has been perennial in Britain, particularly after the advent of the convenient teabag in the 1950s (97% of all tea consumed is now sold in teabags). Tea endured a brief dark age during the 1990s and 2000s, as consumer culture fell in love with coffee; but now, sales are reviving. Tea is even beginning to acquire the same cult status as wine and whiskey in some circles, with as much attention being paid to provenance, preparation, and other mystifying factors such as ‘nose’ and ‘mouth-feel’. And hence the availability of tasting sessions such as this one.

Alex went on to explain tea’s surprisingly enduring methods of production – due to the delicacy of the harvesting process, 96% of tea is still picked by hand. Due to its sensitivity, it is still grown primarily in China, India, and parts of Africa – warm, wet parts of the world, between the tropics of Capricorn and Cancer. Although some tea estates have been attempted in the UK, the challenges of raising a crop here mean that you pay a premium for a cup of tea Alex dismissed as not much worth the drinking. He explained how so many different types of tea – black tea, green tea, white tea, blue tea, and even yellow tea – are all created from the same leaf, by variations in the wilting, drying and cutting processes. He also took the opportunity to dispel the myth that green tea is ‘better for you’ than regular black tea – the only difference between the two is the degree to which they have been oxidised, and in the scientific research done to date, green tea has not been demonstrated to be significantly better for your health.

He then went into detail about the bizarre system by which types of tea will be graded, resulting in such tongue-twisting descriptions as a ‘SFTGFOP’ (that’s ‘Super Fine Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe’ to you and me – I know, means nothing to me either). As a librarian, such whimsically random classification boggled my mind a little. Moreover by this point, as you can imagine, I was gasping for a nice hot cuppa – and fortunately, this was when the lecture ended and tasting began.

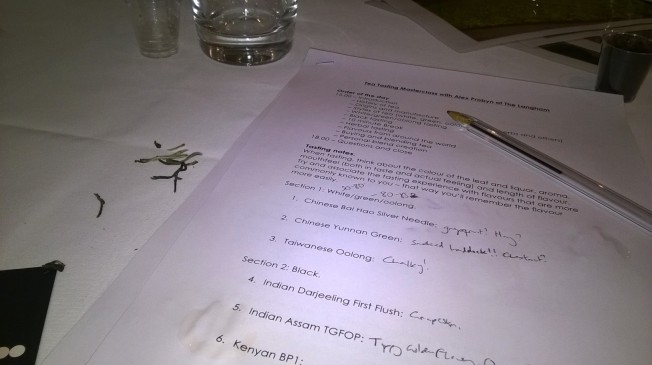

Alex suggested we take notes as we went along, to help us decide later what style of tea our bespoke blends should be. While our palates were fresh, we began with the more delicate types of tea – white tea, green tea, and blue tea (also known as Oolong tea). These had some strange flavours that I would never have associated with tea: the poetically-named Bai Hao Silver Needle (so called because of its long, pale grey leaf) tasted of almost nothing, but with a whisper of grapefruit, and almost… hay? The Yunnan Green was brewed to perfection, avoiding the bitter taste that results from scorching the leaf with boiling water straight from the kettle – but nonetheless had a lingering suggestion of smoked haddock. And the Taiwanese Oolong, apparently a very expensive tea, tasted like nothing so much to me as chalk.

We then moved on to the different varieties of black tea, with varieties from the three big producing nations China, India and Kenya. My very favourite was the lapsang souchong, which smokily evoked bonfires and autumn nights. After all these subtle flavours, the Earl Grey tasted loud and artificial, the bergamot bossily overpowering my tongue.

We then had a short comfort break (something of a necessity after drinking such a large volume of tea). Then on with the tasting, moving into what cannot properly be called teas but rather infusions – Rooibos, rosebuds, hibiscus and red berries. The rooibos was sweet and honeylike, the rosebuds like Turkish Delight, and the scarlet hibiscus tongue-twistingly sour – the red berries neither tasted, looked or smelled like anything much. Ironically, Alex told us, the major ingredient in most ‘red berry’ teas is in fact hibiscus, which gives the tea its vibrant red colour and adds flavour, its sourness toned down by artificial berry flavourings.

The final tasting was a trip around the world, trying some types of tea we were unlikely to encounter in the supermarket. A beautiful Chinese flowering tea blossomed up from the bottom of the glass like some weird undersea creature, tasting of nothing much but looking marvellous. Stone-ground Japanese Matcha green tea looked like pond water and tasted powerfully of fish, but was oddly moreish. A caffeine-rich Argentinian iced tea left me cold, but I loved the sugary, flavourful hits of Moroccan mint tea and an Indian Massala Chai rich with ginger and cinnamon. And finally, a special treat: a shot of Chinese Pu Erh tea, the most expensive tea on earth – a fermented, aged black tea, matured in cakes for years, sold for mind-boggling sums at auctions to tea connoisseurs. Alex told us that cakes of the best Pu Erh could sell for close to a million pounds, meaning a single pot could set you back about £4000. However, like so many things people are willing to pay silly money for, it must be an acquired taste – the only note I wrote for it was “urgh!”

The tasting session had overrun, and we were left with very little time to design our blends. I opted for a marriage of tradition and whimsy, choosing a black tea base of lapsang souchong, lifted up with the sweetness of rose petals and the sour snap of hibiscus – I called it Sweet & Sour Tangy Tea. Alex suggested balancing the sharp hibiscus with some citrusy lemongrass, and I was more than happy to take his advice. It arrived about a week later in a vacuum-sealed container, and was utterly delicious and scarlet once brewed. So all in all, it suits me to a ‘T’ (sorry).